Reclaiming the Sidewalk: The Class Politics of Walking in Nairobi

Two viral tweets mocking a short walk in Nairobi reveal the city’s deep-rooted class politics around mobility. This post unpacks why walking, used by nearly half of Nairobi’s commuters, is stigmatized, how that shapes urban planning, and why reclaiming the sidewalk is key to a safer, more inclusive city

Wayne Odhiambo

8/8/20254 min read

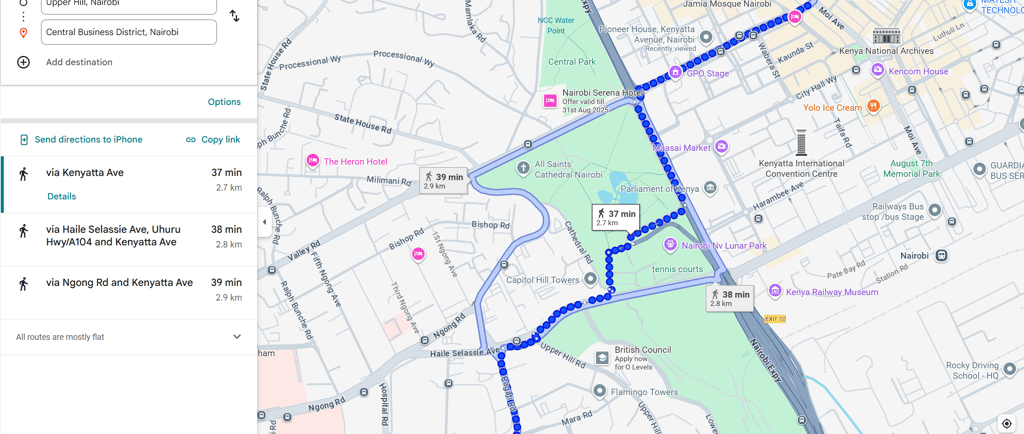

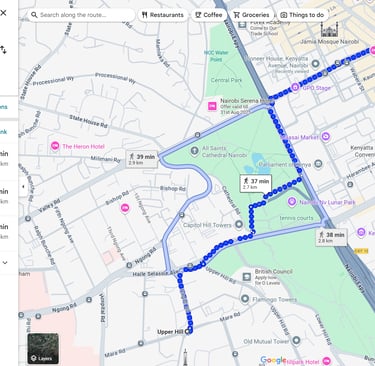

“Walking from Upper Hill to town to save 30 KES has to be studied as a con scam.” -@sifa_bavina

“Is it only in Nairobi where walking is looked down upon?” - @CiruMuriuki

"30 x 2= 60 to and from work. By 30 days that's 1800 large, enough to get you Smirnoff Vodka,''@muriith1_e

Today’s post comes from a pair of viral tweets that lit up Kenyan X and, unintentionally, exposed just how deeply class politics shape the way we view something as basic as walking.

The first mocked the frugality of a short walk. The second, a reply to the first tweet, questioned whether Nairobi is unique in treating walking as suspicious or laughable. Both drew thousands of reactions, revealing a shared undercurrent: in Nairobi, walking is too often read as a marker of poverty, not a practical or even healthy choice.

What Nairobi really looks like on the ground

Forget the jokes for a moment and look at the data:

Walking accounts for 40–47% of daily trips in Nairobi (ITDP).

Public transport absorbs most of the rest, while private vehicles carry roughly 13–15% of people but dominate road space and budgets (ScienceDirect).

Yet infrastructure tells a different story: sidewalks are incomplete or blocked, crossings are rare, and road expansion still prioritizes cars.

Why the stigma matters

Mocking a KES 30 saving ignores a bigger truth:

That’s nearly KES 1,500 a month for someone earning the minimum wage .

Daily walking provides free exercise and reduces congestion.

Pedestrian fatalities make up about 65% of road deaths in Nairobi , yet public outrage is minimal and headlines often blame victims.

When walking is framed as shameful, policy and budget decisions follow suit leaving the majority of commuters less safe.

A Nairobi worth walking

From Kibera’s winding footpaths to Kenyatta Avenue at midday, Nairobi is already a walking city. What it lacks is the respect and investment that reality deserves.

So yes, walk from Upper Hill to town if you want. Save the 30 bob. Call a friend along the way. Notice the jacaranda, the matatu graffiti, the life of the city that only exists at human speed.

The joke was never walking. The joke is a city that still treats walking like a mistake.

Walking’s Prevalence vs. Its Perception

Despite its stigma among elites, walking remains the most common mode of urban travel in Nairobi:

An estimated 40% of daily trips are made on foot, with another ~41% taken in public transport; only about 13% via private vehicles .

Other studies place walking at 45% of trips in Nairobi or as high as 47%, equating to ~2.27 million foot trips per day .

A recent modal-split survey gave 39% walking, 46% public transit, and 15% private or ride-hailing.

Across wider urban Kenya, walking and matatu commuting together account for about 89% of adult commutes . In comparative studies, walking made up ~42% of trips in Nairobi and 61% in Kisumu.

This empirical evidence underscored: walking is by far the norm in Nairobi, even if it’s socially devalued.

Infrastructure, Policy & Risk

Despite its prevalence, pedestrian needs are chronically underserved:

Nairobi has committed to allocating 20% of road construction budgets to non‑motorized transport (NMT) and mandates sidewalks in new road designs—but implementation remains weak source: WIRED.

A recent governance study in Kenya noted that decision-making around walking infrastructure still faces numerous institutional and political barriers source: ResearchGate.

The consequences are clear: pedestrian fatalities account for ~65% of traffic deaths in Nairobi, and many roads lack sidewalks or safe crossings at all source; WIRED.

Tweets Reflecting Cultural Stigma

The tweets by @sifa_bavina and @CiruMuriuki tap into a broader mindset: walking, even to save money is seen as petty or desperate. Such social commentary simplifies walking to an expression of failure or lack.

Yet given that 40–47% of Nairobi commuters walk daily, these perceptions dismiss the reality that walking is not a lifestyle choice but often a necessity. Worse, it positions walking as a source of shame rather than resilience.

The Hidden Benefits They Overlook

Walking offers:

Affordability: essential for low-income workers, students, informal traders, and many others.

Health benefits: active daily travel improves physical well-being.

Environmental gains: low-carbon mobility, vital in rapidly growing urban areas.

Urban vitality: pedestrian activity enhances street life and local commerce.

These are ignored by narratives that celebrate car ownership and deride walking.

Why the Attitude Matters

When walking is mocked:

Pedestrians are less likely to be prioritized in transport and city planning.

Safety becomes optional; victims of crashes are often blamed as “jaywalkers.”

Public outrage over pedestrian deaths remains muted.

Yet the numbers tell a different truth: walking is how the majority moves yet it remains politically invisible.

Reframing Mobility Narratives

To shift perceptions, we must:

Highlight tweets and replies that defend walking—as @R307529 reminds us, walking offers health and reclaiming time. “Time & staying healthy, not money.” — @R307529

Elevate stories of real walkers, not as pitiable subjects but as citizens with dignity.

Demand infrastructure funding that meets reality: safe, contiguous, well-lit sidewalks; capacity for foot traffic.

Challenge status symbolism: driving a car shouldn’t be the benchmark of urban success.

Conclusion: Reclaim the Sidewalk

The viral tweets reflect just one corner of a broader cultural bias but their resonance shows how walking is socially side-lined. Yet from streets near Kibera to the corridors of Upper Hill, millions walk every day out of necessity, resilience, and practicality.

Walking is not a con. It’s not shameful. It is central to Nairobi’s urban life and deserves recognition, respect, and investment.

It’s time for Nairobi, and Kenya, to reclaim the sidewalk: physically, culturally, and politically.